Kathryn Kibota’s Graduate Voice Recital

With John-Micah Braswell (piano) | April 17th, 2021

Notes & Translations

Trois Chansons de Bilitis

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) | Pierre louÿs (1870-1925)

Bilitis, a sixth century BCE Greek courtesan had an idyllic youth in Pamphylia, a country “harsh and forlorn, made somber by the darkness of an impenetrable forest, dominated by the enormous mass of the Taurus Mountains; [with] mineral springs flow[ing] from its rocks, large salt lakes resid[ing] on its heights, and silence fill[ing] its valleys.”[1] As a contemporary of the Greek poet Sappho, Bilitis recounted her life through poetry, which was eventually found on the walls of her tomb in Cyprus. A glimpse into the life of women in Ancient Greece, her compelling autobiographical poetry has been distributed to readers throughout history.

But it was all a lie—Bilitis never existed. Her story was a magnificent fabrication crafted by French writer Pierre Louÿs. Enamored by the culture of Ancient Greece, Louÿs (originally spelled Louis but altered to make it appear more Greek) found Parisian culture too restrictive. His exploration of Ancient Greek life through the fictional Bilitis presents a “sexually liberated alternative to prevailing societal attitudes towards morality.”[2] Les Chansons de Bilitis presents various manifestations of love: the pastoral first section describes the youthful relationship between Bilitis and the shepherd boy Lykas, the second section details a ten-year lesbian affair in a sophisticated urban setting, and the final section explores the sexually liberated lifestyle of a metropolitan courtesan.

“We must sing a pastoral song, calling on Pan, the god of the summer wind”

Louÿs met Debussy, winner of France’s most prestigious musical award, the Prix de Rome, in 1893 through mutual friends. Although their friendship did not produce a mass of artistic output, the Tois Chansons de Bilitis is an emblem of fin-de-siecle French art. The three songs that Debussy set all originate in the idyllic first section of the Chansons, which describes the attraction, consummation, and termination of Bilitis’ relationship with Lykas.[3] Debussy’s hypnotic use of modal scales in the piano creates a timeless, pastoral atmosphere over which Bilitis tells her story.

In “La Flûte de Pan”, Bilitis describes the initial sexual connection between herself and Lykas through his gift of a syrinx, a flute made of reeds crafted by the satyr Pan. Debussy includes the “erotic power of the syrinx, its ability to seduce with its floating melody” by beginning the song with a seven-note flourish in the piano, mimicking the seven tones of the traditional pan flute.[4] In “La Chevelure”, the relationship between Bilitis and Lykas has evolved past the need for the syrinx as a sexual mediator. Rather, the two consummate their relationship. At the moment of climax, we encounter Wagner’s infamous “Tristan” chord, highlighting the passion of the moment. The final song, “Le Tombeau des Naïades” explores the death of our lovers relationship. We are told that the “satyrs so strongly associated with the syrinx have died, and have been replaced by a mundane goat.”[5] As Bilitis searches for the fantastical creatures of her lost youth, she finds them irrevocably lost. Yet while Trois Chansons de Bilitis ends with the death of Bilitis’ childhood, Debussy chooses to end with a rising scale figure, offering potential hope to Bilitis as she enters the next phase of her life.

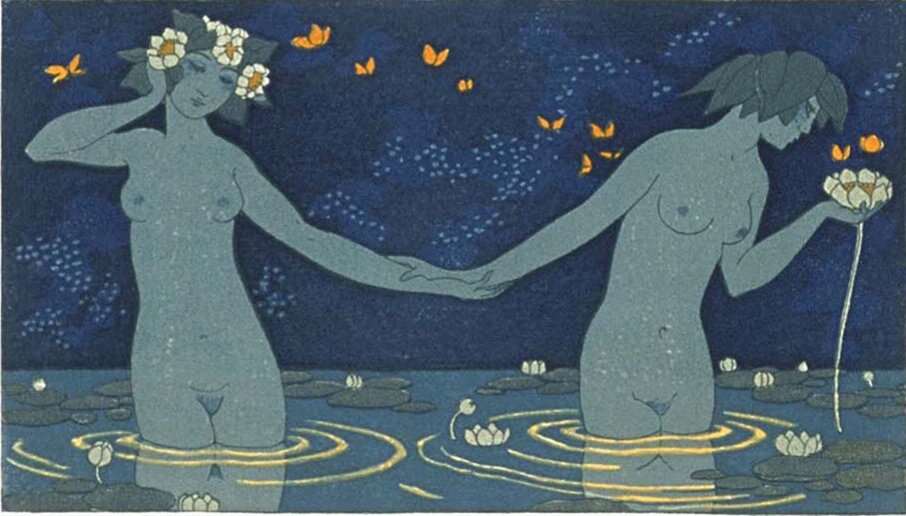

Tonight’s presentation of Trois Chansons de Bilitis features illustrations of the poetry by eminent French artist George Barbier. The fusion of Neoclassical and Art Deco styles in Barbier’s illustrations evoke an ancient past through a contemporary lens, paralleling Louys’ desire to explore contemporary sexual and social liberation through an archaic lens.

FROM THE DIARY OF VIRGINIA WOOLF

DOMINICK ARGENTO (1927-2019) | Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

(warning: mentions suicide)

“Who am I, what do I really feel?”

Adeline Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) was an English writer who is considered one of the foremost modernist writers of the 20th century and a pioneer of the use of stream of consciousness as a literary device.[6] Born in privilege, Woolf suffered a traumatic upbringing, resulting in multiple mental health lapses throughout her life. After the onset of World War II and the subsequent bombings of two of her homes during the German Blitz, Woolf became severely depressed and obsessed with death, eventually taking her life in 1941 by filling her overcoat pockets with stones and walking into a nearby river.[7] Woolf became one of the central subjects of the 1970s movement of feminist criticism, and her works have been attributed to inspiring feminism.

Dominick Argento (b. 1927) is one of America’s most distinguished contemporary composers and has been honored with numerous awards, including the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for From the Diary of Virginia Woolf.[8] His widely diverse works display his innate dramatic sense and have instant audience appeal. Although his style remains predominately tonal in context, his music freely combines tonality, atonality, and twelve-tone writing in a rich harmonic mix.

From The Diary of Virginia Woolf is a powerful work—intensely dramatic, memorable, and unsettling. Written in 1974 for mezzo-soprano Janet Baker, Argento wanted to compose something that would capture Baker’s immense sensitivity and consummate artistry.[9] The eight diary excerpts Argento selected for this cycle chronicle major events or emotional landmarks in Woolf’s life from 1919, the beginning of the diary, to 1941, the last entry before her death by suicide. The entries document Woolf’s journey of artistic self-discovery and observations of her literary, emotional, social, and creative life.

Although Argento’s work is dense and complex, the music and text are connected throughout the cycle. The cycle begins with the first diary entry and ends with the last, giving the work a feeling of unity. The first song contains a statement of a twelve-tone row that forms the work’s nucleus. The last song contains wisps of themes and rhythmic fragments from the previous songs and repeats a section of the opening with almost identical notation. Thematic repetition is a central element to the cycle; themes are manipulated like leitmotivs. From The Diary of Virginia Woolf is an extraordinarily riveting work, immediately drawing the listener into Woolf’s personal world. Argento says, “Of all my cycles, Virginia Woolf most directly addresses the issue of ‘who am I, what do I really feel?’”[10]

*One word has been edited in this performance of “Rome” to avoid a derogatory portrayal of a specific group. Virginia Woolf’s writing was marked by racism. It is my opinion that performances of this work should recognize this fact of the author and present with this information in mind. Click here for further reading on this topic.

IL TRAMONTO

Ottorino respighi (1879-1936) | Percy B. Shelley (1792-1822)

In the spring of 1815 Percy Shelley, one of the major English Romantic poets, was beset by consumption. Obsessed with thoughts of his mortality, he began imaging what might become of his lover Mary Wollstonecroft (soon to be Mary Shelley, who would author Frankenstein three years later) if he died.[11] While Shelley eventually recovered, his thoughts of mortality lingered, especially considering the recent death of the couple’s first child. Shelley’s poem “The Sunset” directly grapples with the mingling of love and death, the power of grief, the longing for peace, and the effect of time. Ironically, although segments of the poem had been published before Shelley’s drowning in 1822, the complete poem was not seen by the public until his widow published it posthumously in 1824.

A century after it was originally penned, the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi became enamored with the “The Sunset” through an Italian translation by Roberto Ascoli. While he had no way of knowing it at the time, Respighi would befall a similar fate to Shelley and the unnamed man in “The Sunset”, dying of bacterial endocarditis at age 56, leaving his wife Elsa Respighi as a widow for the next 60 years. In 1914–shortly after his appointment to the faculty of the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia—Respighi set “The Sunset” in Ascoli’s translation, “Il Tramonto.” Scored for soprano and string quartet (though tonight heard with the piano reduction), the fifteen minute song contains so many contrasting emotions and moods that “the work feels less like a song and more like an opera in miniature.”[12]

Unlike his more famous compositions, The Fountains of Rome or Pines of Rome, Respighi’s palate is noticeably more subtle and refined in Il Tramonto. The entire work is shaped by the emotional changes in Shelley’s poetry, with constantly shifting tempo and chromatic harmony as the poem moves from the passion of the lovers to the aging woman’s plea for release.[13] And while the lovers’ search for the sunset ends in tragedy, when the old woman finds peace in the hope for death, perhaps the sun rises again, as Respighi ends the work with a pianissimo, hopeful major chord.

“‘Is it not strange, Isabel,’ said the youth, ‘I never saw the sun?’”

Thank you!

Professor Elizabeth Hynes | Professor Jeremy Frank | John-Micah Braswell | Geovanna Nichols-Julien | Dr. Lisa Sylvester | Avery Garrett | Tanya and Travis Kibota | Dr. Melissa Schiel

This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of a Master of Musical Arts in Vocal Arts degree.

All translations my own unless otherwise indicated.